I found this piece on an old disc the other day. I wrote it as a piece of architecture to a, now, defunct Masonic Club here in Los Angeles – the Hermes Trismegistus Traditional Observance club in Culver City. It dates back to August 22, 2006, almost ten years to the day.

Reading through it, I thought it would be fun to share it again to see if it still holds it esoteric weight.

King Solomon’s Temple – A Symbol to Freemasonry

Sanctum Sanctorum

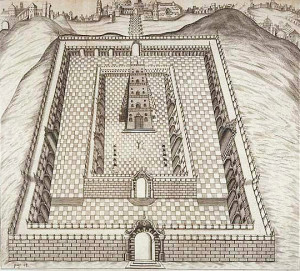

Solomon’s ancient temple was built a top Mt. Moriah in Jerusalem between 964 and 956 B.C.E. Its construction is chronicled in the First Book of Kings, which begins at the end of King David’s reign and the crowning of Solomon. As king, Solomon continues the task his father began which was to build the temple. The text tells us that God restricted David, having collected the materials to construct the temple, from building it because of the blood he shed at the conquering of Israel. Ultimately, Solomon completes work on the temple, which was built to house the Ark of the Covenant, and become “a glorious temple for which God was to dwell”. (1 Kings 8:13).

Chris Hodapp, in his manual Freemasons for Dummies, defines Solomon’s Temple as a representation of the individual Freemason, where both an individual man and the physical temple take “many years to build” as a “place suitable for the spirit of God to inhabit.” The work of a becoming a Freemason is, in my opinion, a metaphor to the construction of the temple. This definition is not far off the mark, but alone it says nothing of why this bold metaphor is used.

Through deeper explorations of this topic, I was lead to a broader understanding of the temple and its relevance to the Freemasonry we practice today. One path of that exploration led me to understand it from the perspective explored in the works of John Dee, Henry Cornelius Agrippa and Francesco Giorgi, each an important Renaissance philosopher.

In Dame Frances Yates text The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, she suggests that early Renaissance Cabalists felt the temple represented a definition of sacred geometry that was mirrored in the temple by reflecting a perfect and proportional measure made “in accordance with the unalterable laws of cosmic geometry.” These ideas formed from the work of Francesco Giorgi in De Harmonia Mundi, which drew in Vitruvian principals of Architecture and integrated the foundation of Christian Cabalism with the ideas from Hermetic study to create “connections between angelic hierarchies and planetary spheres” that [rose] “up happily through the stars to the angels hearing all the way those harmonies on each level of the creation imparted by the Creator to his universe, founded on number and numerical laws of proportion.”

These ideas are from an early Christian Cabala (c.1525), before the open appearance of Freemasonry, and Solomon’s temple, as we know it today. Building on the ides of Giorgi, Cornelius Agrippa explored the ideas of Alchemy, Hermetic, Neoplatonic and Cabalist thought, and wrote about them in his book De Occulta Philosophia (Three Books of Occult Philosophy

These ideas are from an early Christian Cabala (c.1525), before the open appearance of Freemasonry, and Solomon’s temple, as we know it today. Building on the ides of Giorgi, Cornelius Agrippa explored the ideas of Alchemy, Hermetic, Neoplatonic and Cabalist thought, and wrote about them in his book De Occulta Philosophia (Three Books of Occult Philosophy), published in 1533. In this text, one important idea was that the universe was divided into three worlds (degrees), which consisted of an elemental world, a celestial world, and an intellectual world, each receiving influences from the one above it. The first world was believed governed by natural magic (element) and arranged substances “in accordance with the occult sympathies between them.” The second world is concerned with celestial magic that governed “how to attract and use the influences of the stars.” Agrippa himself calling it “a kind of magic mathematical magic because its operations depend on number.” The third world represented ceremonial magic “as directed toward the super celestial world of angelic spirits.” Beyond that, Agrippa says, is the divine itself. These ideas are not about the physical temple, but instead I see it representing an unseen or perhaps inner temple, the travel in what we call today the self.

This philosophy of this divine self, interacting with the magical principals I suggest, merged at that time into the then strong and intelligent stone mason guilds, blending their practical application of numbers and formulation with the exploration of the divine worlds that many worked to physically construct. These ideas were accepted and adopted into the early landmarks of Freemasonry where, I believe, that the temple was perceived as more than a representational place of being. Over time, as philosophy and understanding changed, much of the fraternity lost sight of why Solomon’s Temple was important, that it represented a more mystical and philosophical construct akin to Agrippa’s spheres. Its interpretation has, today, moved into a metaphorical position becoming a part of the metaphorical stage in which our craft is set. But by examining how the temple exists in our degrees today will see some of that connection to the Renaissance philosophy.

Samuel Lee depiction of Solomons Temple

In modernity, King Solomon’s Temple, within Freemasonry, appears in each of the three degrees (or worlds) as different aspects within each degree. Within the first, it is represented as the ground floor, the allegorical entrance into the fraternity. The temple is not depicted as the complicated structure; instead it is as an unfinished edifice, which is implicit to the ritual. Like Agrippa’s first elemental sphere, the first degree of masonry is the initiate’s entry point into Freemasonry and its philosophy, giving the initiate the elemental components to start his formation, only the work is not the rough labor of the operative, but instead the work of the speculative.

The Second Degree makes use of the temples middle chamber, whose dual meaning represents the halfway point into the temple, and the halfway point of Freemasonry. But interestingly we are taught here that the second degree is the most important of the three degree, as it is here we are lead through the 15 steps from the ground floor to the middle chamber of King Solomon’s Temple, where we as masons are instructed on our “wages due and jewels.” The various adornments of the temple have a multifaceted meaning that is described in this degree, which again factor into the representation of the temple.

But what makes this degree so important to me is that it is not the middle chamber, but the odyssey across the three, five and seven steps to it that mark it as important. Across those steps we are taught about the three stages of human life, the five orders of architecture, and the seven liberal arts (amongst other things), and like Agrippa’s second sphere of celestial magic, its mathematical influence can be felt throughout.

This path is the important symbolic link to the temple, where our ritual goes so far to remind us that of the three degrees, the Fellowcraft is the one that applies “our knowledge to the discharge of our respective duties to God, our neighbor, and ourselves; so that when in old age, as Master Masons, we may enjoy the happy reflections consequent on a well spent life, and die in the hopes of a glorious immortality.” The importance being laid on the journey of a Fellowcraft.

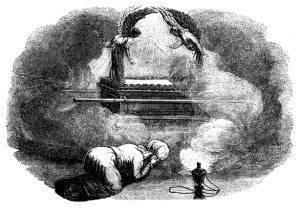

Sanctum Sanctorum or, Holy of Holies

The third degree, or the consequence of that well spent life, ultimately represents the Sanctum Sanctorum or, Holy of Holies, in King Solomon’s Temple. Mentioned at the end of the Fellowcraft, this is where the brother reflects on the “well spent life” by the rewards of his work. The symbolism here is that it is the deepest heart of the temple and the furthest attainment of a Freemason. It also is to represent the deepest penetration into the psyche of the man. This is also the pinnacle of the ritual without the further exploration of the additional rites. The Holy of the Holies is representational of the celestial realm defined by Agrippa, and is the closest sphere outside of the divine itself. It functions as the house of God, both literally in the constructed temple, and metaphorically within the newly raised Mason. This echoes the ideas mentioned by Giorgi and later expanded on by Agrippa and Dee. Dee’s further expansive ideas later went on to influence early Rosicrucian thought in a similar fashion.

Agrippa’s three worlds, I suggest, form (in part) the basis of the steps and the journey through King Solomon’s Temple through the degrees of Freemasonry. The presence of King Solomon’s Temple in ancient thought, from the earliest Old Testament writings to the pinnacle of renaissance occult philosophy has preserved it as an iconographic representation of the path to the divine. Solomon’s temple is not a solitary place in history, used as a simple metaphor in which to base an allegorical play. Instead, it is a link in early Christian Cabala and Hermetic thought, which is just as vital today, as it was then, to the tradition of Freemasonry. Still a metaphor but a more profound one whose importance is not often explored or represented in modern Masonic thought. Looking at the ideas of this renaissance philosophy, I believe that philosophy becomes squarely linked to the past, present, and future of Freemasonry and to King Solomon’s Temple.

Sources:

Duncan, Malcom C., Duncan’s Ritual of Freemasonry. New York: Crown Publishers. 2005.

Hodapp, Christopher, Freemasons for Dummies. New Jersey: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 2005.

The Holy Bible, NIV, Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing. 1984.

MacNaulty, W. Kirk, A Journey Through Ritual and Symbol. London, Thames and Hudson. 1991.

Vitruvius, 10 Books on Architecture. Trans. Morgan, Morris Hickey. New York: Dover 1960.

Yates, Frances, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. London/New York: Routledge, 2003.